Symbols from the Medieval to the Renaissance

published: 1.7.25

Symbology is an important aspect of art history, as it can inform a viewer of key information about a work of art and is critical to understanding elements in the work. However, it is history that informs art history, and symbols change with shifting ideas of thought and social structure. Art during the Renaissance was viewed differently than art in the Medieval period, and that can be attributed to the rise of capitalism, humanism, and scientific inquiry. These factors inform religious, animal, and powerful symbols.

religion

Biblical stories were often associated with specific symbols—such as the evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, who were represented by an angel, a winged lion, an ox, and an eagle, respectively. God was often represented by natural symbols, like a ray of light, fire, or wind, but was also seen as a hand. From the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, however, God was depicted as the Pope or an Emperor. This powerful depiction of God, often viewed as an old man with a beard, actually comes from images of Zeus or Jupiter. This is a result of artists drawing from existing artistic conventions, as well as a way of rebranding pagan traditions to be more closely associated with Christian ones.

The change in the depiction of God from a natural occurrence to a bearded man during the Renaissance was likely closely tied to the rise of humanism and the humanization of the divine. During the medieval period, religious iconography was a way of showcasing Biblical stories in an era of illiteracy. Depicting God with natural symbols visually showed his power and associated him with creation. During the Renaissance, religious art did not have the same focus, but instead was designed with a more aesthetic purpose. A more naturalistic, relatable religious figure was in demand, and therefore the idea of a God who was simply a ray of light, flame, or gust of wind became less common.

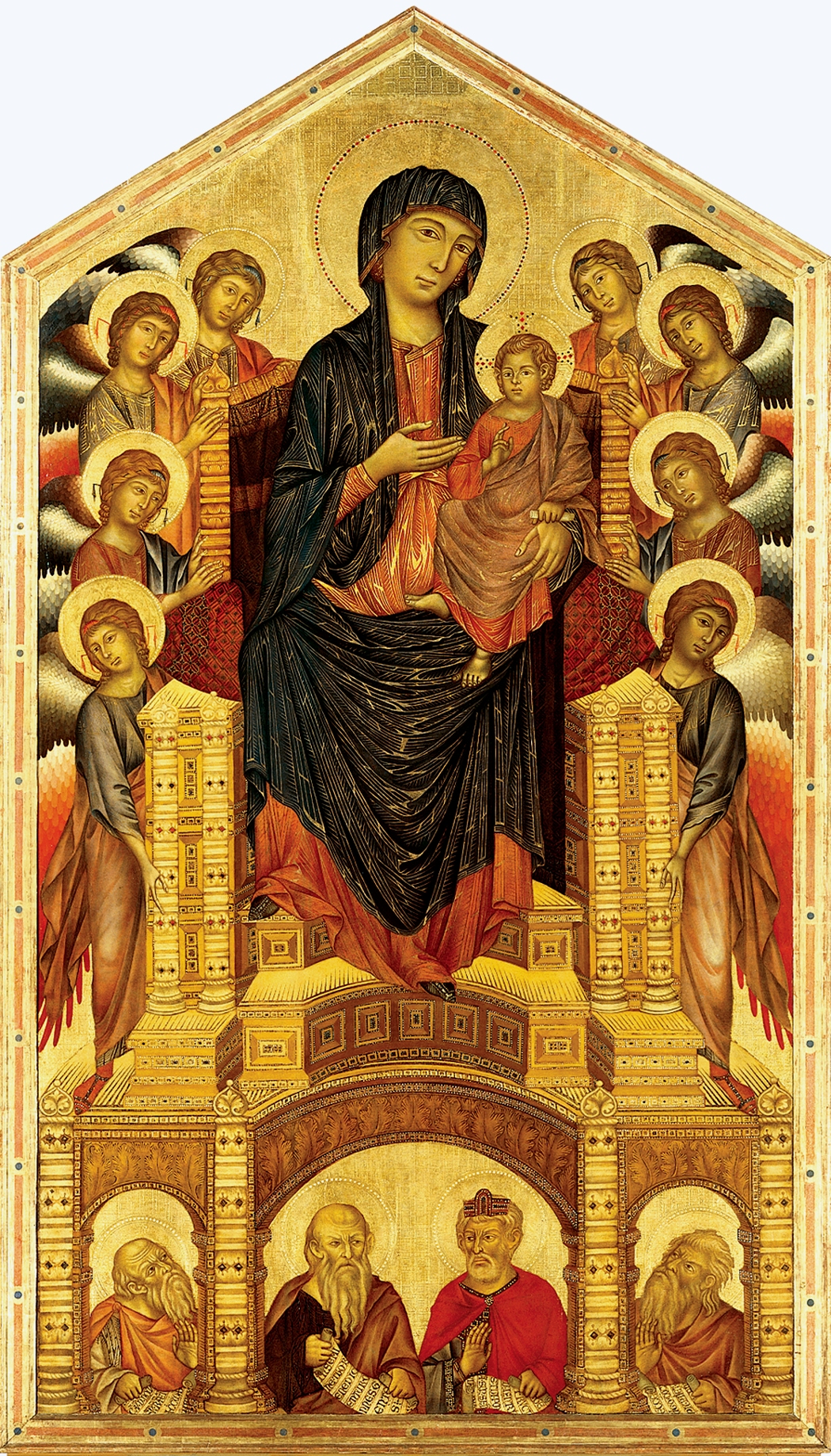

Another example that makes this change evident is the depiction of the Virgin Mary, who shifted from being a distant regal woman to a more relatable mother, frequently depicted with the baby Jesus. In Catholicism, Mary is seen as an intercessor to God, and prayer to her was given with the intention of her speaking to God for the person praying. Duccio’s Madonna Ruccelai, painted in 1285, is an altarpiece that depicts the Virgin Mary seated on a throne. She is not naturalistic and is inhumanely tall. Her eyes and hands create a line of sight leading to Jesus, representing her role as an intercessor. Furthermore, the gold she is surrounded by represents her power and influence.

In the Renaissance, there were four ways of depicting the Virgin Mary: The Madonna and Child, the Madonna of Mercy, Immaculate Conception, and Pietà. All of these depictions humanize her—holding the baby Jesus and experiencing motherhood, with a large mantle as a form of protection, a young woman ascending to heaven, or cradling the body of Jesus following his crucifixion. Akin to representations of God, Mary is portrayed as a young European woman, like in Fra Filippo Lippi’s Madonna with the Child and Two Angels. She is seated on a simple chair, and her nimbus is thin and humble. In fact, many depictions of the Madonna contain thin, almost barely noticeable nimbuses. Medieval depictions of Mary are surrounded by gold, or contain flame-like emissions around her body. In some cases, she is wrapped in a mandorla. This change in the Renaissance humanizes her, and the lack of signs of divinity acts as a connection to human life, not a divine one.

animals

Similar to religious iconography, animal symbolism was somewhat inspired by classical mythology, though rebranded to serve a Christian agenda. The Bestiary is a collection developed in the second century, which contains descriptions of animals, as well as their meanings—i.e., the religious connections to each animal. This included imaginary creatures like the basilisk, which was strongly associated with the devil, as well as the manticore and a centaur. There are other more obvious examples, especially Biblical examples, like the dove representing the Holy Spirit. There are several areas over which animal symbolism pervades outside religion, especially heraldry and sport.

Within heraldry, one of the most popular motifs was lions, especially evident in textiles. The lion represents courage and vigilance, notable in the epitaph of King Richard the Lionhearted. In the twelfth century, the lion was added to the English royal arms—the three lions facing forward and walking forward. They also appear in religious imagery, as lions could also represent resurrection or rebirth. The religious and secular use of lions further the association of lions, as evidenced by the Steeple Aston Cope embroidery—where it is beside martyrs and the Passion of Christ. In sport, art surrounding hunting depicted falcons, and they identified nobility. Stag hunts were associated with human life, as was the hunt of the mythical unicorn (sometimes believed to be a reference to Christ).

Another popular symbol is the dragon, notably connected to St. Margaret of Antioch. The dragon was associated with the devil, and more generally evil, as were many reptilian animals (real or imaginary). This association is also why many Christian saints are attributed with slaying them. These include St. George, the patron saint of England, who saved a village and a princess who was to be sacrificed to the dragon. He convinced the villagers to convert to Christianity, and ‘defeated evil.’ St. Margaret of Antioch was a martyr, as she had sworn herself to a life of chastity, but God repeatedly saved her until she was eventually beheaded. In one of her near-deaths, she was swallowed by a dragon, but she had a crucifix, and the dragon allowed her to escape because he couldn't stand the crucifix, evidently equating the dragon with the devil.

In the Renaissance, the birth of humanism drastically affected the way animals were depicted in art. While many animals maintained their symbolic meaning, the rise in secular art and humanism changed the approach to animals in art and expanded their symbolic meanings to contain a secular purpose. For example, dogs, being associated with faithfulness, wisdom, as well as anger and aggression, came to be associated with Judas, as painted by Titian in his scene of the Last Supper, between 1560 and 1580. However, outside of religious art, they represented fidelity, demonstrated in Jan van Eyck’s portrait of a married couple. Another example of how this changed was in monkeys. During the Middle Ages, monkeys were seen as symbols of the devil, but in Renaissance art, monkeys could also be representatives of people. As primates, they were seen as humans if they did not experience human desire. Animals like dogs or monkeys, or even cats, in art can be reliably interpreted as what their behavior is actually like. This does continue the tradition from medieval art, as lions continue to signify power and nobility, and peacocks continue to represent wealth and aesthetics.

In addition to the expansion of symbolic meaning to encompass secular life, the focus on humanism during the Renaissance also encompassed scientific curiosity, including anatomy. This interest was largely driven by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, who wanted a greater understanding of anatomy in order to portray them more accurately in his artwork. Both Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo completed dissections and illustrated anatomical features of animals. Therefore, some animal presentations are not symbolic representations at all, but rather a method of understanding animal anatomy.

patrons & power

Before one can examine symbols of wealth and nobility in Medieval art, one must first look at patronage. In the Middle Ages, patrons of art were typically members of the Catholic Church and noble, wealthy families. The church funded stained glass windows, altarpieces, and illuminated manuscripts. Royalty would commission decorative art, and local nobles would request artwork for local churches. Patrons would request their art, typically related to their faith, but a secular commission would include a historical, literary, or portrait scene.

One example of this is the Bayeux Tapestry, which was likely commissioned by Odo, the half-brother of William, the Duke of Normandy, who invaded England in 1066 in the Battle of Hastings. The tapestry depicts Odo praying over the soldiers before they departed for England. The association created between his prayer, the success of the invasion, and the affiliation with his half-brother William both establish a connection between him and a person of power and influence, and attribute him to the victory in battle. Patronage can be beneficial to the patron, as it associates them with power, control, or some form of victory.

During the Renaissance, patronage was quite similar to Medieval patronage, but civic bodies, wealthy individuals, and church officials also sponsored art. It was a sign of social status, and a way to demonstrate wealth, power, and sophistication. When speaking of patronage and art during the Renaissance, it would be remiss to not mention the Medici family, who are financially responsible for the Birth of Venus, the Tomb of Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino, and Donatello’s David. The Borgia and Sforza families ruled over Milan, and Leonardo da Vinci was an engineer for both, creating the Last Supper for Ludovico Sforza in 1495-98.

When patrons in the Middle Ages commissioned portraits, their symbols, clothing, and settings were all designed to reflect their status or profession. For example, patrons were often surrounded by luxuries and goods that gave them their wealth, therefore showing their profession and contributions. Patrons could also draw connections between themselves and religion, to showcase their piety and faith, making them appear as holy rulers. One symbol evident in portraits of the wealthy was the color red and gold leaf. Red was reserved for people of high power, and was often worn by nobles, clergy, and members of the elite. Gold was reserved for rulers and saints, and it was also frequently added as a sign of divinity. This would give those in power a visual association with religious figures. Furthermore, if a woman was depicted in blue, it would associate her with the Virgin Mary, who was nearly always depicted in blue. In addition to clothing, jewelry, especially those which featured stones, were painted in detail, indicating women with power. In male portraits or military figures, they were accompanied by swords or daggers, indicating power and military valor.

In the Renaissance, unlike in Medieval art, brightly colored clothing, like reds or blues, would make a patron’s authority appear questionable. Dark colors were what provided a sense of power or authority. However, the use of some colors can indicate the wealth of a patron. Blue pigment was incredibly expensive, hence why the Virgin Mary was often depicted in a blue robe and red dress.

One notable departure from Medieval tradition in power and patronage is the inclusion of classical elements as a symbol of power or intellect. For example, in the painting The School of Athens, not only is the classical setting supporting the figures from antiquity, but it also furthers its symbolism as a work of intellect and power. Its placement in the Papal office, associating the Pope with a classical setting, gives him a greater sense of importance in the context of the rebirth of classical thought.